|

|

The Art & Craft of Home DesignText by Laurie LaMountain One of my previous forays in the field of publishing began in 1992, when I was working for a trade magazine that focused on traditional joinery and the construction of timber-framed houses and furniture. Over the next four years, I gleaned just enough about construction to be dangerous, but more importantly, I developed a keen sense of craftsmanship. What I’m realizing now, nearly twenty years later, is that I was witnessing a growing renaissance of the Arts and Crafts Movement that began in England roughly one hundred years earlier. It was during those four years that I began to cultivate an appreciation for the truth to material, structure and function that is essential to the original Arts and Crafts Movement. It was there that I first encountered the above quote by William Morris. It was there that I learned about Gustav Stickley, and Greene and Greene and their impressive and enduring influence on the Movement in the U.S. And it was there that I began to develop a different sense of material value in my own life and surroundings. The Arts and Crafts Movement flourished in Europe and North America between 1880 and 1910. According to Morris biographer Fiona MacCarthy, between 1885 and 1905, one hundred and thirty Arts and Crafts organizations were formed in Britain. Ironically, the Movement was something of a renaissance of medieval decorative art, inspired by the ideas of William Morris and John Ruskin in reaction to the increased mechanization of production brought on by the Industrial Revolution. Morris felt the Middle Ages represented a high point in the art of the common people and that “without dignified, creative human occupation people became disconnected from life.” Ruskin, who upheld the similar belief that medieval architecture was the ideal model for honest craftsmanship and quality materials, argued that the separation of the intellectual act of design from the manual act of physical creation was both socially and aesthetically damaging. By the end of the nineteenth century, Arts and

Crafts ideals were evident throughout European

architecture, interior design, furniture and decor,

and the Movement began to take hold in the United

States. The first American Arts and Crafts Exhibition

was held in Boston in 1897 and purportedly featured

over a thousand objects made by one hundred

and sixty artists, half of whom were women! Interestingly,

many of the artists were also social reformers.

On the West Coast, Greene and Greene would

popularize the ultimate bungalow style that later

influenced the design of homes all across middle

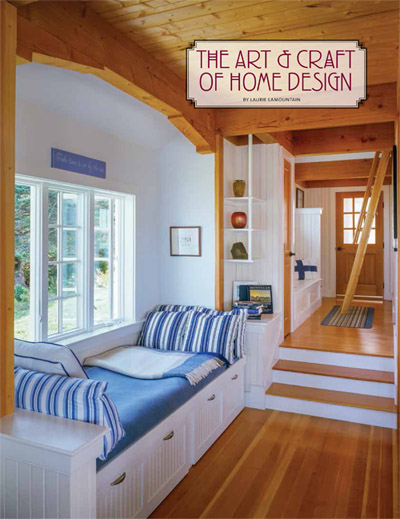

America, including the Sears Roebuck Kit Homes Eventually, the Movement’s dedication to nature and an idealist medieval era was no longer valid and the modern machine age and technology brought an end to the handcrafted era. Fast forward a hundred years and you’ll find a thriving resurgence of architects, artisans and woodworkers who are committed to the tenants of Morris and Ruskin, whether consciously or not. While the Arts and Crafts Movement was a rebellion that rose from the conviction that art and craft could change human life, it was also a reaction to the excessive ornamentation of Victorian design; an elimination of the unnecessary, in favor of a simpler, more refined aesthetic. That ideal continues today. Subjected to a world where plastic and modular prevail, there are those among us who value good design, masterful technique and natural materials above all else. When you walk into a home that’s been built by true craftsmen who understand and appreciate those concepts, the impression is immediate. It’s obvious that the design was thoughtfully conceived and carefully crafted. There’s a subtle refinement that you simply won’t find in a tract house development. In my previous publishing experience and as publisher of Lake Living, I’ve had the privilege of working with and interviewing a number of architects and builders, many of whom exemplify the Arts and Crafts ideals in their conscious consideration and appreciation of space. A charming alcove in a cottage designed by John Cole Architect is an example of structural repetition (the cover photo features another from the same house). Scissor trusses in a timber frame cut by Andy Buck echo the influence of Asian design within the Movement. Similarly, when furnishings and decor

are selected with conscious consideration,

it shows. It’s often in the subtle, easily

overlooked details where craftsmanship

is most apparent. There is an intentional

execution to the details that makes them

seem unintentional or, as Charles Greene

so much more eloquently stated, “good

things are not always seen at once, but

they do not need advertising when they

are found.” I’m reminded of a corner in my

house where three angles meet in proximity.

An inconspicuous but considered detail

was carved at the end of each piece of

trim. Several doorways and windows are

capped with botanical freizes designed and

carved by my brother. At a friend’s house,

the porches that lead into the house are

prefaced with “doormats” made of rounded

stones arranged in a half-oval below the As a homeowner there is a temptation to fill what is seen as empty space with objects that appeal to one’s sense of aesthetic, but if the house is not viewed as a whole and treated as such, it could well lack the harmony that was central to the Arts and Crafts ideal. One beautiful element that relates to the whole is worth a thousand random things that have no relation to one another. In William Morris Decor and Design, author Elizabeth Wilhide describes one of the Morris family homes as such, “Structural repetition is emphasized by the use of the same materials and furnishing throughout. Each room, though different in character and function, is related to the whole, as a variation on a theme.” This principle is one that is applied by John Cole Architect and praised by Sarah Susanka in the article on small space design that is also in this issue. The simple but striking brackets detailing the alcoves of Nyce Cottage create a separate sense of space at the same time that they define it as a whole. In her book The Not So Big House, which was published in 2001 at the peak of the housing bubble and several years before it would burst, Susanka said this about the house of the future: “The Not So Big House offers a way to bring the soul back into our homes, our communities, and our society’s fabric. The house of the future will be Not So Big—and an expression of who we are and the way we really live.” Her message is as familiar as it was prophetic. Recommended reading: |