|

|

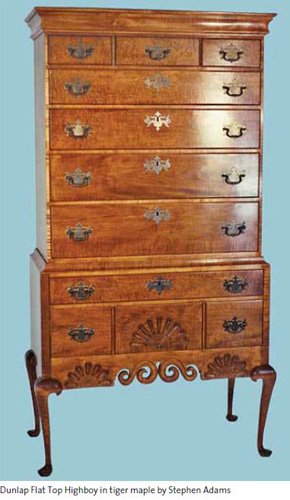

Custom Craftedby Laurie LaMountain There was a time when all furniture and cabinetry was custom made, but in the age of IKEA and mass production, it’s not as easy for custom furniture makers to compete. It takes time to create a piece of period furniture that will survive several generations of use—and time, as we all know, translates to money. The good news is, there are still plenty of people who appreciate and are willing to pay for custom-crafted furniture, and there are still craftsmen who have the know-how to faithfully reproduce the elegance and sophistication of 18th-century styles—Queen Anne, Chippendale, Hepplewhite and Sheraton—that evoke an era of tradition, order and prosperity. Superior construction and detail are every bit as evident in their furniture today as they were two centuries ago. Stephen AdamsStephen Adams has been crafting 18th-century inspired furniture in Denmark, Maine, since 1984, when he purchased the shop on Main Street previously owned by Douglas Campbell. Campbell, himself, spent more than thirty years perfecting the art of antique furniture reproduction. A lot of the machinery in Adams’ shop, including the bandsaw and joiner, is vintage WWI era equipment that Campbell acquired during his tenure. Adams managed the shop in Denmark for an interim owner before buying it in ‘84, but he notes that his very first shop was actually in his parents’ basement. The second one was on Cumberland Avenue where the now defunct Portland Public Market stands. Adams and several other furniture makers created a collective they called Joint Venture that lasted for only about a year. After that disbanded, Adams made the move to Denmark. His love of woodworking goes way back. “The lightbulb went on when I went to Wentworth [Institute of Technology in Boston, but even as a kid, six or eight years old, I was fascinated with making stuff out of wood. I grew up in Cape Elizabeth near the ocean and would use driftwood for my material. My dad had a boat and a little workshop with a rickety underpower table saw and some tools, so as a little kid I’d be on the floor of the shop in my pajamas with a hand drill and a hammer making stuff. But I never really thought of making a living at it until I went to Wentworth.” These days, Adams’ customers are from all over, including Japan, Sweden and Canada. In fact, he sells more furniture in Maryland, Virginia and DC than in Maine. His clientele tend to be people who appreciate fine period furniture but live 21st-century lifestyles. To satisfy both their aesthetic and utilitarian needs, Adams is able to design and craft a cabinet that looks like a Chippendale but performs like a media center. Doors and bases employ traditional mortise-and-tenon joinery and drawers and cases are dovetailed. All of the materials are high-end; there is absolutely no plywood or manufactured composites involved. Everything is hand turned instead of stamped out by a machine. If the piece calls for hardware, Adams buys it from a company that specializes in authentic hand-forged items. Adams has also produced pieces for larger companies, such as Eldred Wheeler and Thos. Moser, that either don’t have the capacity to handle one-off pieces or don’t want to because they’re more production oriented. They are not able or inclined to invest sixty hours into a Windsor comb-back chair that is completely hand turned. When asked what inspires Adams to invest hundreds of hours into one piece of furniture, he points to being able to take the spark of an idea and turn it into a finished piece. “It sort of becomes your child after a while. I even hate to see them go sometimes. Especially if it’s a major piece that I’ve put hundreds of hours into, say if somebody comes to me for an authentic reproduction of something but I don’t have all the details, as far as sizes and proportions, so I have to do some research. I have to scale things out. There’s quite a lot to the design. So by the time you’ve gone from the spark of an idea to the finished piece, you feel like it’s your baby. It’s probably similar to postpartum depression. You can’t wait for it to be doneand you’re excited about it and finally it’s done and you don’t really want it to be. You get a kind of adrenaline when you’re doing it and then when you’re done, it’s almost a let down.” One such piece is a Dunlap Flat Top Highboy that Adams spent nearly 300 hours on that sold for $10,000. Adams reflects that in the beginning it wasn’t so much about the money as it was that he got a kick out of doing it. If he didn’t charge enough it didn’t matter, so long as the piece came out the way he wanted it to and the customer was happy with it. Now he has reached the point where he’s able to pick and choose what he’ll take and won’t lowball himself just to get the work. “I really want to make sure that the finished product is one I’m happy with, because if I’m happy with it, the customer’s happy with it.” In addition to crafting reproduction furniture, Stephen Adams Fine Furniture also does furniture restoration, which includes repair and refinishing, as well as custom millwork. Stephen Adams can be reached by phone at 207-452-2397 and the shop is located at 46 West Main Street in Denmark, Maine. Greg MarstonIn the days when Adams was subbing for Eldred Wheeler and Thos. Moser, he had up to six employees working with him in his shop. One of them was Greg Marston. Marston grew up in rural Maine and fondly recalls antique outings with his parents to “look at furniture.” While he was working with Adams in the late ‘80s, he had the opportunity to reproduce many of the styles he saw on those boyhood outings, but it wasn’t until he was on his own and focusing his work on antique furniture repair and restoration that he really came to understand it. By taking pieces apart and repairing them, he was able to reproduce the joinery, turning details and overall design. Queen Anne is Marston’s preferred style. “Queen Anne is where it’s at. It’s hot . . . boiling hot. The sensuousness of the lines of a piece, the hardware they used, the form . . . the form is incredible,” says Marston. He recalls a highboy he found at R. Jorgensen Antiques in Wells as his absolute favorite piece. He asked the proprietor if he could take some dimensions and ended up taking the whole thing apart. He took all the drawers out, pulled the top off the base and got detailed measurements in order to reproduce the piece for himself. Finish and color are also key for Marston. In fact, he sees furniture finishing as a trade in itself. He strives to get the colors right in his pieces by using shellacs, colored varnishes, oil pigments, aniline dyes and even homemade concoctions like chewing tobacco and ammonia, which he finds particularly striking on pine. “Color, form and function are really important. That’s where Queen Anne furniture comes in. They have a highboy at the Portland Museum of Art and the color is incredible. You want to reproduce it. You want to get that color,” says Marston. He recalls a clock he finished for a client that has probably ten layers of finish on it. He started with a dye and then in between oil colors layered very thin coats of shellac. Antiques magazine, which Marston refers to as furniture maker’s pornography (“look at the leg on that one!”), is a frequent idea source. “The finishes on the furniture are just incredible. Especially curly maple. When you get that right, you just melt.” Marston is currently completing a bed that a client had begun building but was unable to finish before he died of cancer this past summer. His widow asked Greg if he would finish it and he, of course, said yes. In the spirit of true craftsmanship, Marston has been deeply involved in the restoration of an antique Cape he had moved to his South Bridgton property from Sweden, Maine, several years ago. He is currently plastering the walls of the living room and hopes to be finished with this ambitious restoration by Thanksgiving. Everything, including the paint colors are in keeping with the original. He is, however, still available for furniture commissions, as well as restoration and repair projects. He can be reached at 207-647-8378. Jeff ScribnerJeff Scribner has been building homes for more than thirty years, and, while he claims he’s not a furniture maker, you wouldn’t know it by the numerous pieces in the home he built and shares with his wife, Wendy, in Denmark, Maine. Scribner actually worked for Douglas Campbell when he first opened his shop in Denmark in the late ‘70s, mostly making pencil post beds, Windsor chairs and Queen Anne beds. Friends who are familiar with Scribner’s furniture often encourage him to resume furniture making as a vocation, but he points out that he prefers the flexibility of being able take commissions versus making a commitment to selling furniture full time. Scribner’s passion with furniture is personal. He enjoys researching the construction and history behind the styles he reproduces and working with the various species of wood that may be combined in a single piece. He uses a sack back Windsor armchair he made, Wendy’s favorite because it’s so comfortable, to illustrate the different species beneath the near-black Windsor green paint. Here in New England, it’s typically birch or maple for the legs, stretchers and posts because they’re easy to turn; basswood, poplar or pine for the seat because they’re easy to shape; ash or oak for anything that’s steam bent because they’re pliant. To illustrate an aspect of the construction he turns the chair over to show how the legs are tapered and then wedged where they enter the seat so that they’re forced when sat upon and can’t come loose. He points out that Windsor chairs were originally designed to be outdoor furniture and that they were almost always painted, no doubt to protect them from the elements, but also to highlight form over wood. Just about everywhere you look in the living room, there’s a beautiful piece of reproduction furniture that Scribner made. A Queen Anne corner chair with a carved Spanish foot features a rush seat made from cattails harvested from a marsh in Raymond, Maine. Twin tables made as a birthday present for Wendy are in the Hepplewhite style and feature walnut and mahogany herringbone inlay borders around a tiger maple top. A Queen Anne highboy that lives up to its name at nearly seven feet tall dominates one wall. The base of a William and Mary lowboy, replete with acorn drop finials, is made of black walnut from a tree that once stood behind the Center Lovell Inn. The tree had to be cut down to make room for an addition Scribner was building—part of the deal was that he got the tree. The top and case are constructed of tiger maple and the drawers have the same herringbone inlay borders as the twin Hepplewhite tables. “The thing I like is knowing the construction of the furniture and how it has to be done. And I like being able to take a photo from a magazine or book and being able to build that piece fairly close to dimensions just by having the knowledge of the construction,” says Scribner. The fact that he isn’t relying on these furniture pieces for his livelihood makes a difference in how Scribner approaches them. He allows the sometimes painstaking pleasure of their creation to take precedence. For this reason, if you are able to engage Scribner to create, restore or refinish a piece of furniture, you are fortunate indeed. He can be reached at 207-632-6870.

|