|

|

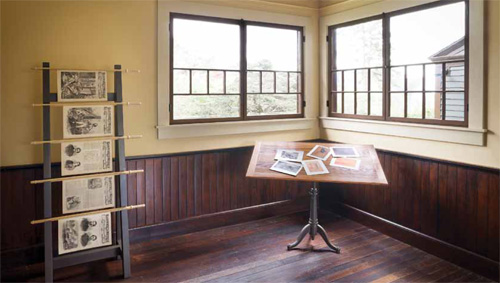

The Importance Of Placeby Laurie LaMountain Photography by Trent Bell When you enter the Winslow Homer Studio at Prouts Neck, in Scarborough, Maine, which has just undergone six years of painstaking restoration, the impression is one of stark simplicity. There are relatively few pieces of furniture and decor left from the artist’s personal possessions, but as Kristen Levesque, director of public relations for the Portland Museum of Art, points out, the Studio is more about the importance of place. It is here, on the surf-battered coast of Maine that Winslow Homer lived and worked for the last twenty-seven years of his life. It is here that he found inspiration in nature and created some of his most iconic paintings. Mark Bessire, director of the Portland Museum of Art, states it best in his foreword to Thomas Denenberg’s Winslow Homer and the Poetics of Place: “Maine—beloved for the same reasons that brought Homer here more than a century ago—possesses an aura of authenticity and a full measure of potential and risk. Today, as in the late nineteenth century, Maine provides an answer for people experiencing an alienation from nature and desiring a different texture to everyday life.” Fully aware of the significance of place in relation to Homer’s paintings, the Portland Museum of Art purchased the Studio in 2006 with the objective of restoring it to the way it was when Homer lived and painted there and preserving it for posterity. The connection between Winslow Homer and the Portland Museum of Art dates back to 1893, when the Museum’s predecessor, the Portland Society of Art, exhibited Homer’s painting Signals of Distress. Today the Museum’s permanent collection includes an impressive selection of Homer’s works. With the acquisition and restoration of the Winslow Homer Studio, scholars, artists and visitors will now be able to experience and appreciate Homer’s inspiration first hand. The Studio’s south-facing, first-floor windows frame the same elemental views today that Homer captured on canvas during the 1890s, such as the seascapes Weatherbeaten and Cannon Rock. Homer, by then a mature artist, created some of his best known and most appreciated work during his years at Prouts Neck. Art critic Frederick Morton wrote of Homer in 1902, “all of Homer’s experience and practice in figure painting and landscape have led up to his inimitable seascapes, which he paints as no other artist ever did or can.” Homer achieved early renown in the mid-1800s. Elected in 1865 to the National Academy of Design in New York City at the age of twenty-nine, he was one of few artists who was equally at ease and adept in a range of media, including etching, painting, watercolor and drawing. He worked in New York City for over twenty years as a freelance commercial illustrator for popular magazines, including Harper’s Weekly and Ballou’s Pictorial, at a time when the market for illustration was growing rapidly. Harper’s sent Homer to the front lines of the Civil War, where he sketched battle scenes and camp life, among them A Sharpshooter on Picket Duty. War work was dangerous and the commercial work that followed the war exhausted Homer’s tolerance for humanity. By the time he moved to Prouts Neck permanently in 1883, Homer felt he had earned the right to solitude within his studio at the edge of the sea. In a letter he wrote to his sister-in-law in 1908 he stated, “All is lovely outside my house and inside of my house and myself.” When the Museum purchased the Winslow

Homer Studio from Charles Homer

Willauer, a great grand-nephew, it had undergone

several significant alterations since In 1883 noted architect John Calvin

Stevens was engaged by the Homer family

to move their carriage house 100 feet away

from their summer home and convert it into a painting studio/home for the “hermit of Prouts Neck.” Stevens added

an expansive porch on the second floor,

grandly referred to as the Piazza, which

afforded unparalleled views of the sea but

started to fail not long after its construction.

Attempts to address the problem were just

that, and when architects first visited the

Studio in 2006 to assess its condition,

they discovered vertical posts and beams

had been added at the perimeter of the

Piazza to support the broad cantilevered Daniel E. O’Leary, the Museum’s director

in 2006, initiated the Museum’s purchase

of the Studio, and quickly followed

the acquisition with a campaign to restore Phase I of the restoration, which was

started in 2007, focused on underpinning

the foundations, addressing structural

damage caused by moisture and water Phase II, completed in spring of 2008, focused on installation of the restored brackets and reinforcement of the Piazza’s east and south-facing façades. The installation of a hidden, internal steel support system designed by the structural engineers, Structures North of Salem, Massachusetts, gave the Piazza the structural support it lacked and allowed for removal of the nonoriginal wooden perimeter posts, returning it to its original and intended appearance. In 2009, Phase III of the project began

and Mark Bessire took over as director

of the Museum. During this phase of the

restoration, which was completed just this Prior to the start of Phase I work, project

architect Craig Whitaker had located two

photos of the Studio in the Smithsonian Museum’s

archives of American artist Walter Interior finishes were restored and a

small kitchen was added during this phase.

Andy Ladygo, a prominent and well-known

plaster conservator, carefully restored the A suspended horizontal ceiling, which was removed in Phase I, revealed two previously concealed roof trusses and beautiful clapboard-clad sloped ceilings. These important historical details were repaired as part of this phase of work— features that have now been highlighted with contemporary lighting designed by Available Light of Salem, Massachusetts. A concealed galvanized-tube-steel structure was installed on top to provide a low-profile structural reinforcement of the original roof. The four-inch tube steel roof framing also provided a place to hide electrical wiring, lightning protection wiring, sprinkler piping and alarm cabling. Craig Whitaker points out that an important

additional challenge of the restoration

was the need to carefully adhere to the

Museum’s “patina” statement concerning All told, the restoration spanned six years and involved museum staff and trustees, architects, engineers, archeologists, conservation specialists, masons, carpenters, restoration woodworkers, electricians, painters, roofers, plumbers and many more, who worked on the Studio each year from September through June, until the completion of the project earlier this summer. A capital campaign of 10.5 million was needed to cover the cost of this extensive restoration project as well as provide earmarked endowments for educational programs, future maintenance of the Studio, and a curatorial impact fund. While some may criticize the multi-million dollar price tag for a project that may not seem to have obvious social benefits, particularly during the last few years of economic hardship, it’s important to consider the value of preserving those profound places that connect us to our higher selves. Economics will ebb and flow, but without these reminders of our potential, we would truly be an impoverished culture. The Winslow Homer Studio opens to the

public on September 25, 2012, concurrent

with the Portland Museum of Art’s exhibition Weatherbeaten: Winslow Homer and

|