|

|

My first stop to learn more about getting the perfect glide was at Sportshaus in West Bridgton. Sportshaus is owned by Marlise and Phil Libby. Back in 1979, after realizing they’d had enough of city life in New York, the Libbys headed north to their vacation home and purchased the ski shop from Hedi and Monell Needham. It didn’t snow their first year in town. Marlise says Pleasant Mountain Ski Area was open for seven days only. Their second year the mountain was open for 26 days. Fortunately for the Libbys, equipment was installed in the fall of ’81. As it turned out, the winter of ’82 was one of the snowiest winters on record according to Scott Andrews, curator and research director at the Ski Museum of Maine. About that time Brian Fox joined

the Sportshaus team as a ski technician.

Interesting to note, Brian is the son-in-law Brian remembers those early years of Alpine ski tune-ups. “The machinery was different,” he says. “All we had was a glorified giant belt sander.” “And a file,” adds Scott Hendricks, who joined the Sportshaus team twelve years ago. To leave your Alpine skis for a tune-up, you must complete a form that simply asks for your name, address, phone number, height, weight and level of skiing expertise. It sounds easy enough, but ski tuning is a science. The ski techs begin by looking at the ski, how it’s used and diagnosing its

problems. They always start with the

edges, sharpening for a 90° angle. Next

they bevel those edges, ranging from zero

to five degrees or more. Recreational skiers

don’t need as much of a bevel as racers or

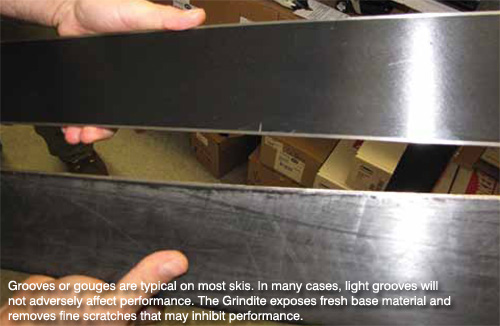

better skiers who are more aggressive. A For base work on the structure of the ski, the techs turn to their $50,000 Grindrite machine. Grooves or gouges are typical on most skis. In many cases, light grooves will not adversely affect performance. The Grindite exposes fresh base material and removes fine scratches that may inhibit performance. Brian notes that like everything else, this equipment is becoming greener. “Years ago emulsion in the water—the cutting agent, coolant and lubricant— should have come with a skull and crossbones symbol.” Today, he says, it is all biodegradable. Even the cleaners used before waxing are citrus based. Next, the base edge and material on it are checked for flatness. If anything is above the edge, Brian says, “You’ll get a squirrely, wobbly feeling.” As skis become wider, it’s more difficult to get a truly flat base edge, but that’s what these ski techs strive for. They polish the skis for a smoother running surface and make sure that edges are sharp. Finally, the skis are ready for the stone

grinding machine, which can bring new

life into them. “This is where the money

happens,” says Brian. Stone grinding allows The final step is hot waxing, which protects against damage. Wax is what enables the ski to glide better, slide better and it makes lateral movements easier. Preparing skis for racers is much more

involved. Finishing touches are done by

hand edging and hand waxing. Once

racing skis are waxed, they must sit for

24 hours to ideally allow the wax to

permeate into the base. After the first coat,

nine additional coats of wax are added.

Following each coat, excess wax is scraped

off since glide comes from wax that’s been

absorbed and isn’t sitting on the base. Then

brushes are used—from aggressive nylon

or bronze down to softer horse-hair--to At Sportshaus, they offer four different tune-up packages ranging from a basic sharpener/wax job for $20 to a full tuneup, which gets you as close to a factory finish as possible at $35. My second stop in learning how

to achieve the perfect glide

is at Carter’s X-Country Ski

Center in Oxford, where David and Anne

Carter have offered groomed trails since

1984. What began as a club because of

David’s long-time skiing passion evolved

into a business that includes renting

and selling Nordic ski equipment. On Since their Oxford Ski Center serves as

a farm stand in the summer months, Anne

took me to the attached greenhouse to

demonstrate waxing techniques for Nordic Anne uses a sponge applicator to

spread Maxiglide, a liquid paste, onto

the base of the waxless skis. “Wipe down

and don’t wipe it all off,” she says as she

demonstrates the movement from top to

bottom. “Maxiglide refurbishes the base.

It’s like a piece of furniture that needs

oil.” This is a do-it-yourself project that Racers take waxing to a whole different

level. It’s a science of creating just the right

mix of waxes to make the ski go faster.

Kick wax is a sticky wax lightly applied

to either side of the center groove in the

kick-zone of waxable classical skis. It’s

labeled for varying temperature ranges— the warmer the temp, the stickier the wax A bar of hot wax looks like a brick and comes in different colors for different uses. For skating skis, ski techs and DIYers always begin with yellow, which is a warm wax. Warmer waxes fill in the pores better, especially with the help of an iron. To apply, the wax is scraped on to the entire base by rubbing it firmly down the length of the ski, again from tip to tail. Anne says that some people apply with a wax iron, letting the heat warm up the wax and drip it on—similar to how Scott applied the P-tex at Sportshaus. Once the wax is applied, Anne then runs a ski iron along the entire base, connecting and smoothing the wax until an even coat is achieved. If you’re doing this at home, don’t use your household iron as you’ll ruin it and may ruin your skis. While one ski cools, the same procedure is followed for the second ski. Returning to the first ski, she gives it

a second coat by simply running the iron

over the wax that is already there. Any

excess wax is scraped off with a plexiglass Finally, the techs take a brush to the skis and remove whatever excess didn’t come off with the scraper. Similar to the Alpine approach, multiple brushes are used depending on the desired texture the skier wants. Classic skis require grip wax in the kick zone or wax pocket, which extends from the heel of your boot to a foot above the top of the binding. Grip wax produces traction by allowing the rough edges of snow crystals to penetrate the wax layer just enough to grab hold of the ski when it is stationary and weighted. It doesn’t prevent the ski from gliding smoothly when already in motion. Hard wax, aka grip or kick wax, is applied in four to five thin layers by lightly “crayoning” it onto the kick zone. Between layers, the wax is buffed in with either a synthetic or natural cork. The friction of the cork warms the wax so it adheres to the ski base, thus keeping the wax on the ski longer. All reconditioning work is carefully done by hand at Carter’s X-Country Ski Center. The cost for a complete hot wax reconditioning is $35. And for the DIYers, they offer a variety of products and recommendations.

|

website design - the

nerve

|

Every skier knows that bogged-in-the-mud feeling.

It’s like an invisible moose is sitting on the back of your

skis as you poke along down the trail. Whatever kind of

skiing you do—alpine, telemark, or cross-country—when

your skis feel sluggish or your sharp turns are more like

controlled slides, the odds are your boards need some

reconditioning. By heading into a local ski shop for a

tune-up, you’ll kick that moose off your tail and enjoy

the perfect glide.

Every skier knows that bogged-in-the-mud feeling.

It’s like an invisible moose is sitting on the back of your

skis as you poke along down the trail. Whatever kind of

skiing you do—alpine, telemark, or cross-country—when

your skis feel sluggish or your sharp turns are more like

controlled slides, the odds are your boards need some

reconditioning. By heading into a local ski shop for a

tune-up, you’ll kick that moose off your tail and enjoy

the perfect glide. In the early days, skis were tuned with

what was essentially a three-foot belt

sander. It was all done by hand—‑the guys

put pressure on the ski and controlled it.

Today, they use a Grindite 2100 stonegrinding

machine to give skis a factory finish.

In the early days, skis were tuned with

what was essentially a three-foot belt

sander. It was all done by hand—‑the guys

put pressure on the ski and controlled it.

Today, they use a Grindite 2100 stonegrinding

machine to give skis a factory finish. After the grinding step, deep gouges

need to be repaired. If tuning one or two

skis, the candle method is used. Skis are

placed in a vise, base up. A plastic P-Tex

candle is warmed with a lighter until

it drips. Scott carefully fills each deep

gouge with the melted plastic, taking care

to make sure that the flame is blue. A

yellow flame means it’s emitting carbon,

a contaminant. By the time he’s done, the

base of the ski looks like a road surface

with sealant over the cracks. Once the

After the grinding step, deep gouges

need to be repaired. If tuning one or two

skis, the candle method is used. Skis are

placed in a vise, base up. A plastic P-Tex

candle is warmed with a lighter until

it drips. Scott carefully fills each deep

gouge with the melted plastic, taking care

to make sure that the flame is blue. A

yellow flame means it’s emitting carbon,

a contaminant. By the time he’s done, the

base of the ski looks like a road surface

with sealant over the cracks. Once the Anne begins with waxless skis, which have a grip pattern carved or molded into

the base material. This texture bites into the

snow to provide grip for the kick portion

of the classic ski stride. Because waxless

skis have a built-in kick there is no need for

a grip/kick wax. There are times, however,

when the snow is wet and sticky and can

clump or ice up on the base of the ski. That’s

when you know that the proverbial moose

is riding on your tails. It’s time to wax.

Anne begins with waxless skis, which have a grip pattern carved or molded into

the base material. This texture bites into the

snow to provide grip for the kick portion

of the classic ski stride. Because waxless

skis have a built-in kick there is no need for

a grip/kick wax. There are times, however,

when the snow is wet and sticky and can

clump or ice up on the base of the ski. That’s

when you know that the proverbial moose

is riding on your tails. It’s time to wax.